Engineering

Engineering

Engineering

From Microservices Mesh to Streamlined Layers: Why We Rebuilt Our Internal Video Indexing System

Stu Stewart, Abraham Jo, SJ Kim, Paritosh Mohan, James Le

Stu Stewart, Abraham Jo, SJ Kim, Paritosh Mohan, James Le

Stu Stewart, Abraham Jo, SJ Kim, Paritosh Mohan, James Le

As TwelveLabs scaled, our earlier microservices-based indexing platform hit operational limits—not in raw performance, but in engineering throughput, deployment flexibility, and system complexity. Indexing 3.0 reimagines the architecture as a set of streamlined layers: a unified indexing platform atop a flexible execution layer and swappable infrastructure, enabling faster iteration, cleaner reasoning, and deployment across diverse environments. This shift treats indexing as a coherent, portable system designed to scale teams and capabilities—not just compute.

As TwelveLabs scaled, our earlier microservices-based indexing platform hit operational limits—not in raw performance, but in engineering throughput, deployment flexibility, and system complexity. Indexing 3.0 reimagines the architecture as a set of streamlined layers: a unified indexing platform atop a flexible execution layer and swappable infrastructure, enabling faster iteration, cleaner reasoning, and deployment across diverse environments. This shift treats indexing as a coherent, portable system designed to scale teams and capabilities—not just compute.

Join our newsletter

Receive the latest advancements, tutorials, and industry insights in video understanding

Search, analyze, and explore your videos with AI.

Feb 5, 2026

Feb 5, 2026

Feb 5, 2026

10 Minutes

10 Minutes

10 Minutes

Copy link to article

Copy link to article

Copy link to article

Introduction — Indexing is where video becomes usable

Video is a uniquely punishing input for production systems. It’s high bandwidth, long-lived, and multimodal—pixels, audio, speech, motion, and timing all matter. More importantly, the “unit of work” isn’t a single inference call. Indexing is an end-to-end transformation: take an opaque blob of video and turn it into structured representations that downstream systems can query reliably.

That boundary layer—indexing—is where video becomes usable.

As TwelveLabs grew, indexing moved from “the thing that runs in the background” to a core piece of infrastructure that every product surface depends on. Search and generation don’t just consume model outputs; they consume the indexing system’s guarantees: what gets processed, how consistently, how debuggably, and how deployably.

And that’s where we hit the breaking point.

Our earlier indexing platform (internally, “Indexing 2.0”) wasn’t failing in the obvious ways. It could process videos. It powered real workloads. But its architecture carried assumptions that became limiting as our team and deployment needs expanded: coordination costs rose, infrastructure coupling hardened, and the system became harder for new engineers to reason about end-to-end.

Indexing 3.0 is our response—but it’s not a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s an architectural reframe: from a microservices mesh that implicitly depended on a specific operating environment, to a layered system designed to scale engineering throughput and run across multiple deployment shapes.

In this post, we’ll walk through the thinking behind Indexing 3.0: what stopped scaling in the previous approach, what actually drove the rebuild, and how the “mesh → layers” model became the organizing idea for everything that followed.

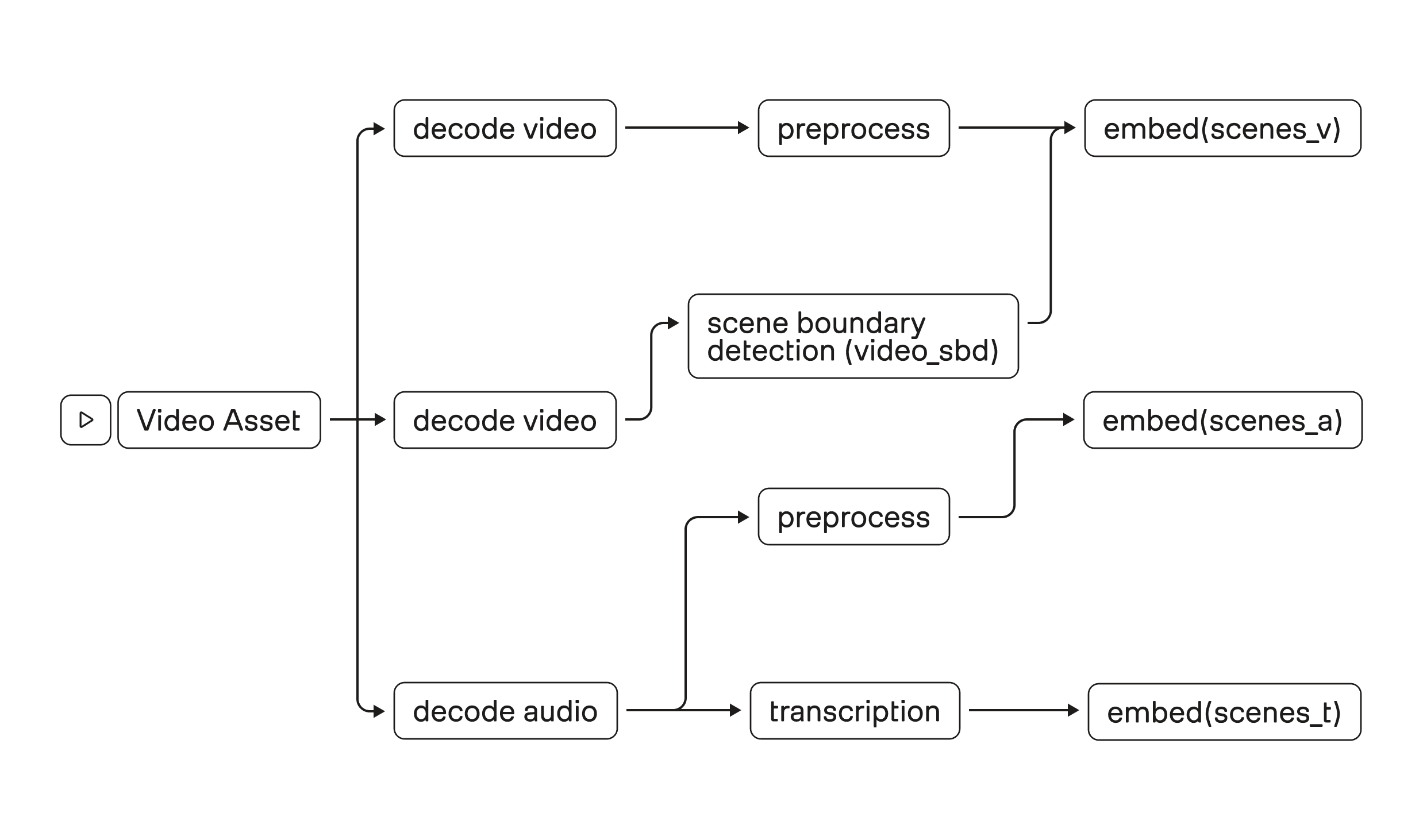

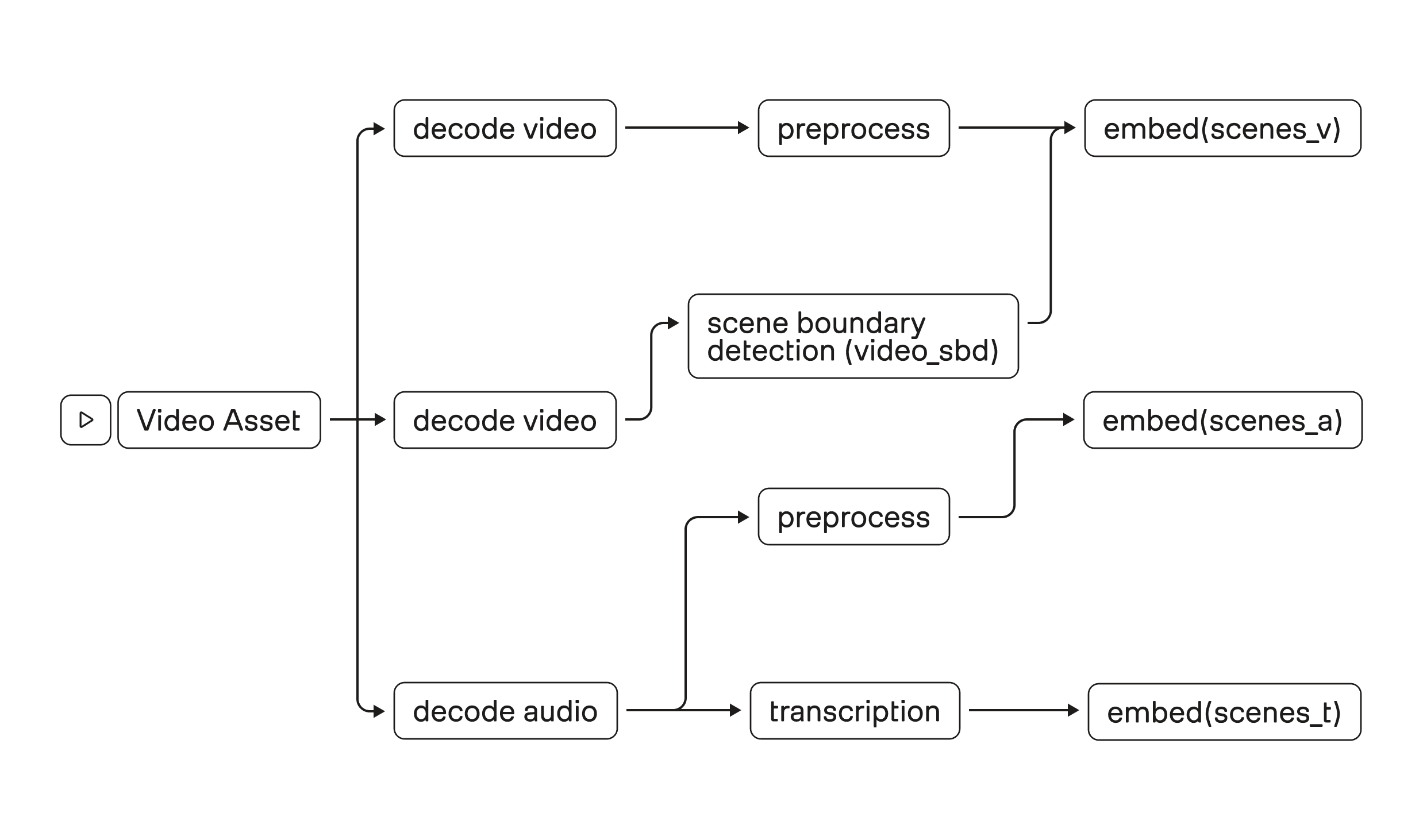

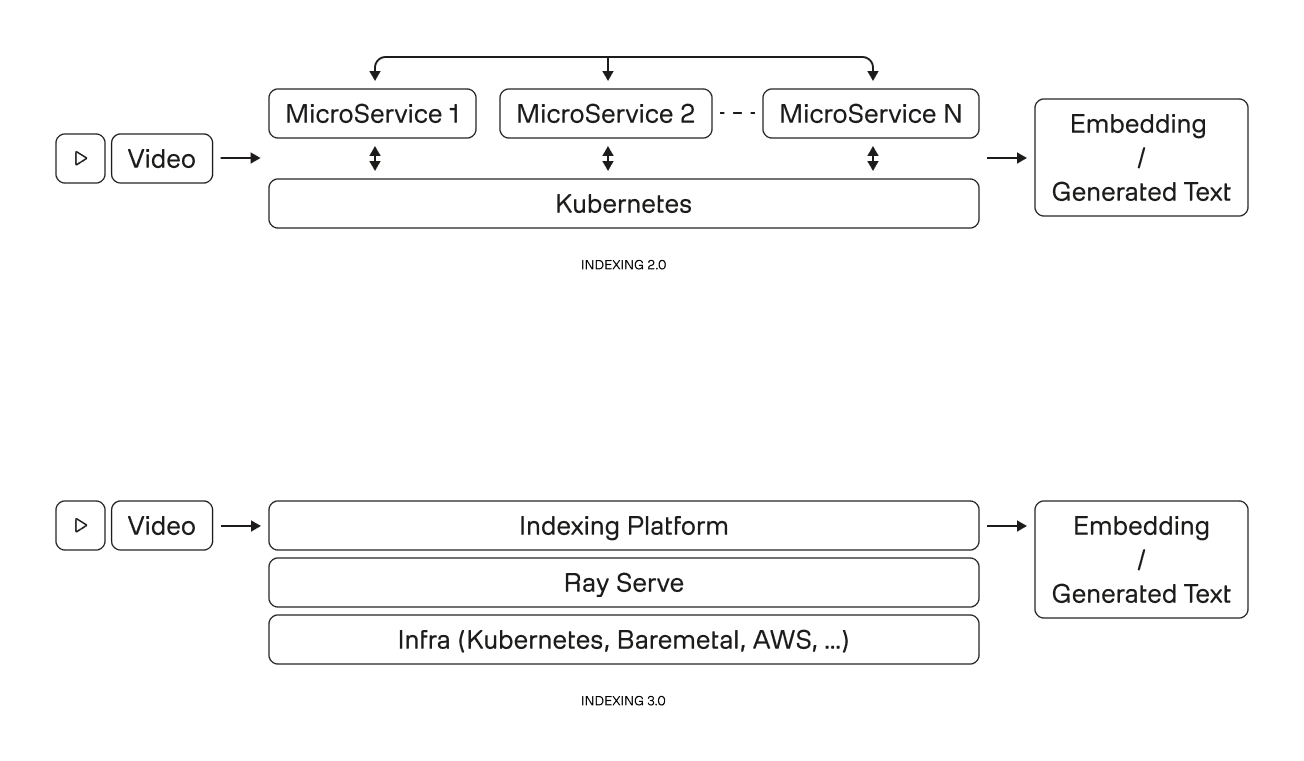

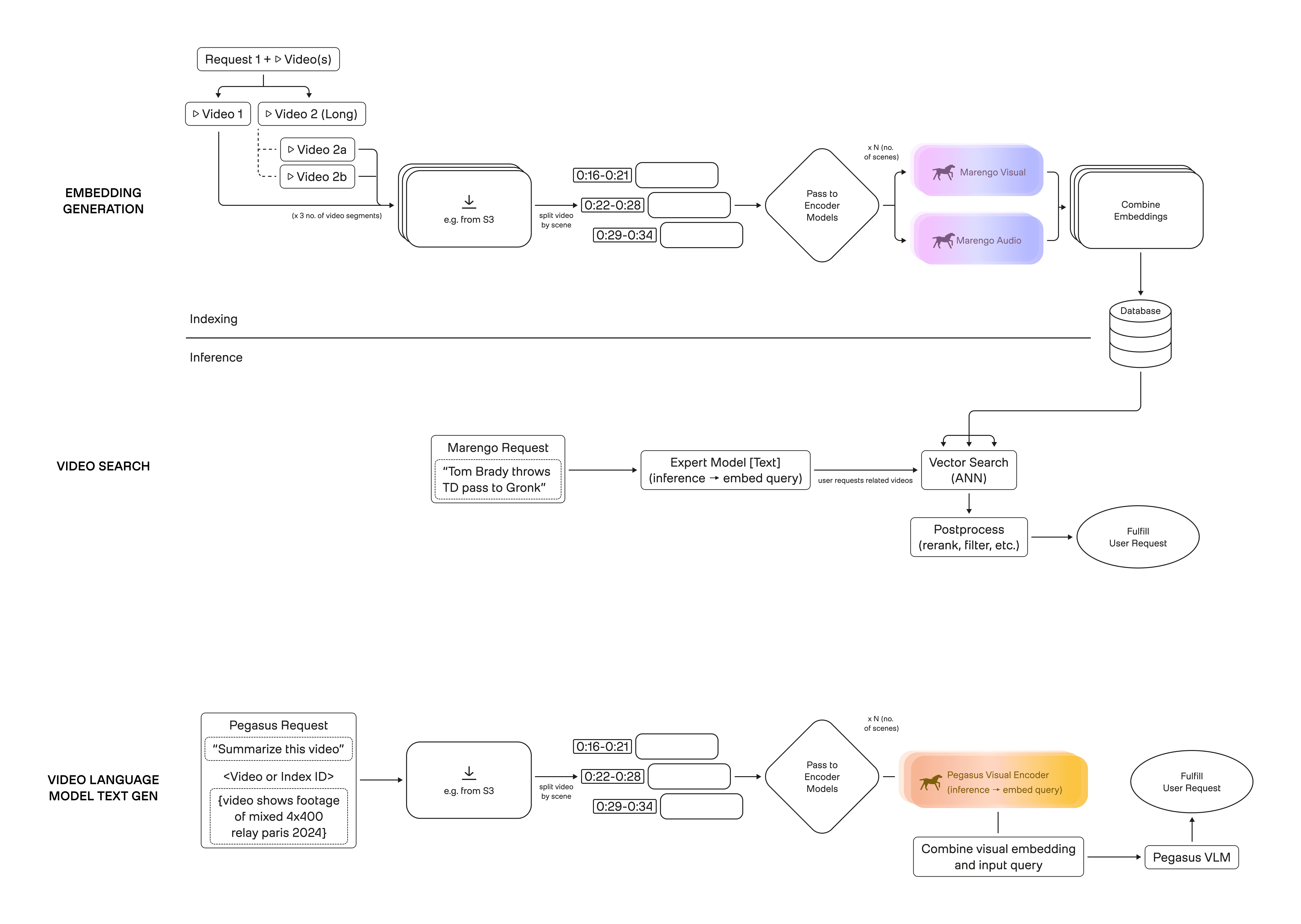

Figure 1. High-level embedding flow: decode video/audio, detect scene boundaries, then embed visual, audio, and transcript segments.

1 - The real breaking point: why our earlier indexing system stopped scaling

Before Indexing 3.0, TwelveLabs operated an earlier generation of our video indexing platform—what we’ll refer to here simply as Indexing 2.0. Like many early-stage production ML platforms, it was designed to solve a very real problem at the time: reliably transforming raw video into usable representations at scale.

And by that definition, it worked.

It powered real workloads, supported multiple model capabilities, and enabled core product surfaces. But as the company grew, a different kind of pressure surfaced—one that had less to do with model quality and more to do with how the system behaved operationally and how it scaled as an organization.

A useful way to see why is to look at what indexing actually has to do end-to-end. It’s a coordinated flow that turns a video asset into cached representations that downstream systems (search and text generation) can use repeatedly.

1.1 - When microservices stop feeling modular

Over time, the Indexing 2.0 platform evolved into a distributed collection of services, each responsible for a specific part of the indexing process. On paper, that decomposition looked clean and modular. In practice, it introduced a form of complexity that compounded with every change.

A small feature update often required touching multiple services. Releases had to be coordinated. Debugging required reconstructing behavior across boundaries instead of reasoning about a single flow. What initially felt flexible slowly became rigid—not because any one service was poorly designed, but because the system as a whole had too many moving parts.

One additional multiplier here was runtime and language boundaries. Some components written in Golang naturally lived closer to production plumbing, while others written in Python lived closer to ML workflows—and the interface between them wasn’t always clean. Crossing that boundary repeatedly (data formats, error propagation, tracing/observability, retries, deployment artifacts) made the “distributed modularity” feel less like separation of concerns and more like separation of context.

At a certain point, the cost of coordination overtook the benefits of decomposition.

1.2 - Infrastructure and scaling assumptions become visible in the worst case scenario

A deeper issue emerged as the system matured: application behavior became coupled to infrastructure behavior.

One example was a scaling pattern that is extremely flexible but can become operationally expensive: spinning up resources per video. That design can be a reasonable default when workloads skew toward longer jobs and when isolation is valuable. Each video becomes a self-contained unit of scheduling and execution.

But the workload reality changes as products mature.

When workloads include a high proportion of very short videos, per-video orchestration overhead starts to dominate:

scheduling and startup costs become a larger fraction of end-to-end time,

scaling down cleanly becomes harder (resource churn and minimum footprints),

and you can end up paying “setup tax” repeatedly for work that finishes quickly.

In other words, a pattern optimized for flexibility at the unit-of-video granularity can behave poorly when the unit of work gets small. This isn’t a “bug,” it’s a mismatch between execution granularity and workload distribution—and it’s exactly the kind of mismatch that only reveals itself after a system hits real product scale.

1.3 - The human scalability ceiling

Perhaps the most telling signal was not an outage or a performance regression, but a people problem.

As the team grew, fewer engineers were able to comfortably reason about the full indexing flow. Understanding how a change propagated through the system required deep, accumulated context. Onboarding became slower. Contributions clustered around a small set of specialists.

Indexing 2.0 had reached a point where it could scale compute, but not contributors. That’s the inflection point we associate with “stopped scaling”: the system continues to run, but it becomes increasingly hard to evolve—especially when product requirements shift (deployment environments diversify, workloads change shape, new model capabilities arrive).

For our ML Infrastructure team at TwelveLabs, this was the moment we realized that incremental improvements would no longer be enough. To move forward, we needed to rethink indexing not as a collection of services, but as a coherent, portable system that could scale teams, deployments, and future capabilities together.

That realization set the stage for Indexing 3.0.

2 - What actually drove Indexing 3.0

Once we accepted that the bottleneck was organizational and operational—not just computational—we had to get precise about what we were optimizing for next.

Indexing 3.0 is our name for the architectural response. It isn’t a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s a deliberate rebuild designed around new constraints: more teams shipping in parallel, more deployment environments, and workload shapes (like short video) that stress different parts of the system.

Three drivers emerged clearly—and in a different priority order than we initially expected.

2.1 - Scaling engineering throughput, not just compute

The primary driver behind Indexing 3.0 was maintainability, but not in the abstract sense of “clean code.”

What mattered was engineering throughput: how many people could make changes confidently, how quickly new contributors could form a mental model of the system, and how safely teams could work in parallel without stepping on each other.

This is where the earlier polyglot / multi-service shape mattered. Even when each component was individually understandable, the interfaces were where complexity accumulated: data contracts, serialization, failure semantics, tracing, deployment packaging. Indexing 3.0 explicitly treats reducing those boundaries as a first-class lever for velocity.

2.2 - Packaging and deployment became first-order constraints

A second, business-critical driver followed closely behind: deployment flexibility.

As TwelveLabs expanded into new environments, it became clear that assumptions baked into the earlier system no longer held. Some environments offered full orchestration platforms. Others allowed only minimal container execution. Treating these as edge cases would have limited where the product could realistically ship.

This forced a shift in perspective:

Instead of “how do we deploy this system?”, we asked: what does the system assume about where it runs?

Indexing 3.0 is designed so deployment shape becomes a variable, not a defining feature of the architecture.

This matters because indexing isn’t a standalone service—it’s the substrate beneath multiple downstream products. Since we offer two video foundation models (Marengo and Pegasus) with different capabilities, the same indexed representations can power retrieval-style workloads (search) and reasoning-style workloads (analysis). Portability expands what products can exist and where they can ship.

2.3 - Cost as a structural outcome, not a tuning exercise

Cost was an important consideration, but notably, it was not the starting point.

In earlier iterations, cost optimizations had largely taken the form of incremental tuning—adjusting resource usage, tweaking configurations, or reacting to specific bottlenecks. Indexing 3.0 took a different approach.

The team recognized that many cost issues were symptoms of deeper structural choices: too many always-on components, inefficient coordination between stages, and architectures that made it difficult to right-size resources independently.

Rather than chasing isolated savings, Indexing 3.0 aimed to create an architecture where efficiency emerged naturally from simpler execution paths, clearer scaling boundaries, and more flexible deployment models.

2.4 - A change in what “success” meant

Taken together, these drivers led to a subtle but important shift in how success was defined.

Indexing 3.0 would not be judged primarily by raw performance numbers or by how novel the architecture looked on paper. It would be judged by whether it enabled:

Faster onboarding and safer contributions,

Parallel development without constant coordination,

Consistent behavior across environments,

The ability to evolve without repeated rewrites.

In the next section, we’ll look at how this shift in priorities led to a fundamentally different way of thinking about the indexing architecture itself.

3 - The architectural reframe: from “microservices mesh” to “streamlined layers”

Once the drivers behind Indexing 3.0 were clear, the next step was to confront a harder truth: the existing architecture was optimized for a different set of assumptions than the ones the business now faced.

What needed to change was not a single component, but the shape of the system itself.

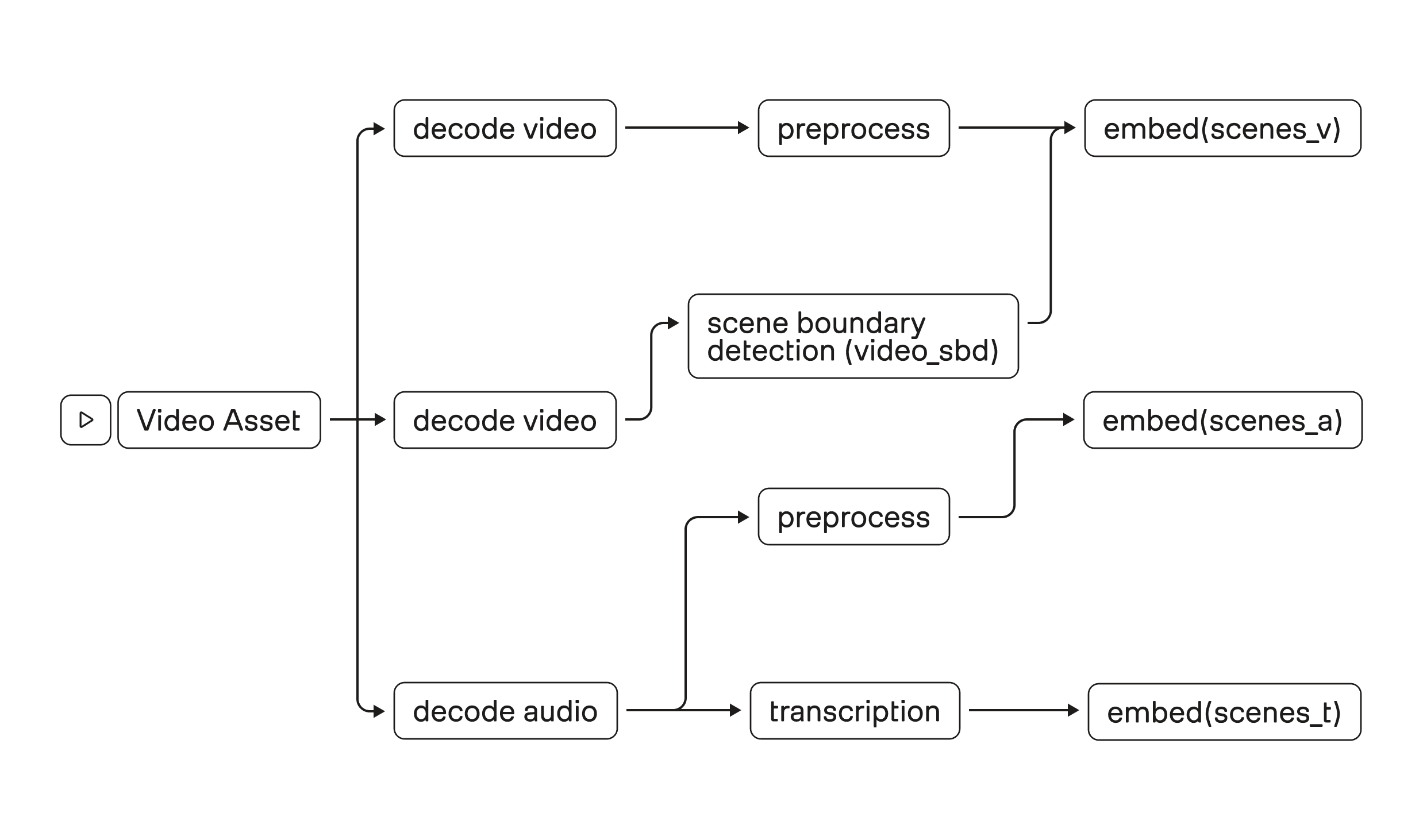

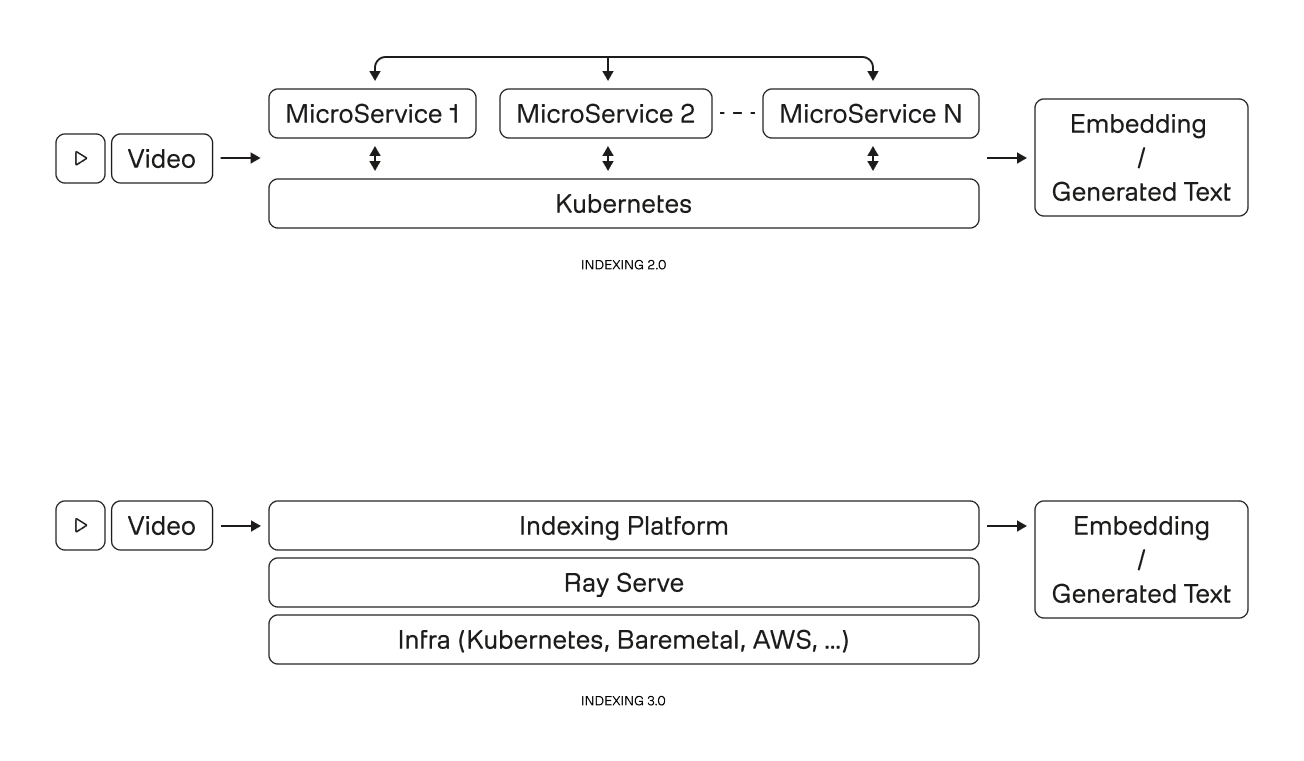

3.1 - The problem with the “microservices mesh”

The earlier indexing platform followed a pattern that will be familiar to many teams: break the system into many small services, connect them through orchestration and routing layers, and let the infrastructure manage execution.

Over time, this created what we now think of as a microservices mesh.

work flows sideways as much as forward,

coordination logic spreads across services and control-plane interactions,

and understanding “what happens to a request” requires global context.

This approach has advantages early on. It allows teams to move independently and scale components in isolation. But as the indexing system grows—and especially as workloads become more heterogeneous—those advantages erode.

Even at a high level, indexing involves decoding, segmentation, embedding, and persistence steps that must compose correctly. When each step is its own service boundary, the system becomes harder to debug, harder to package, and harder to evolve.

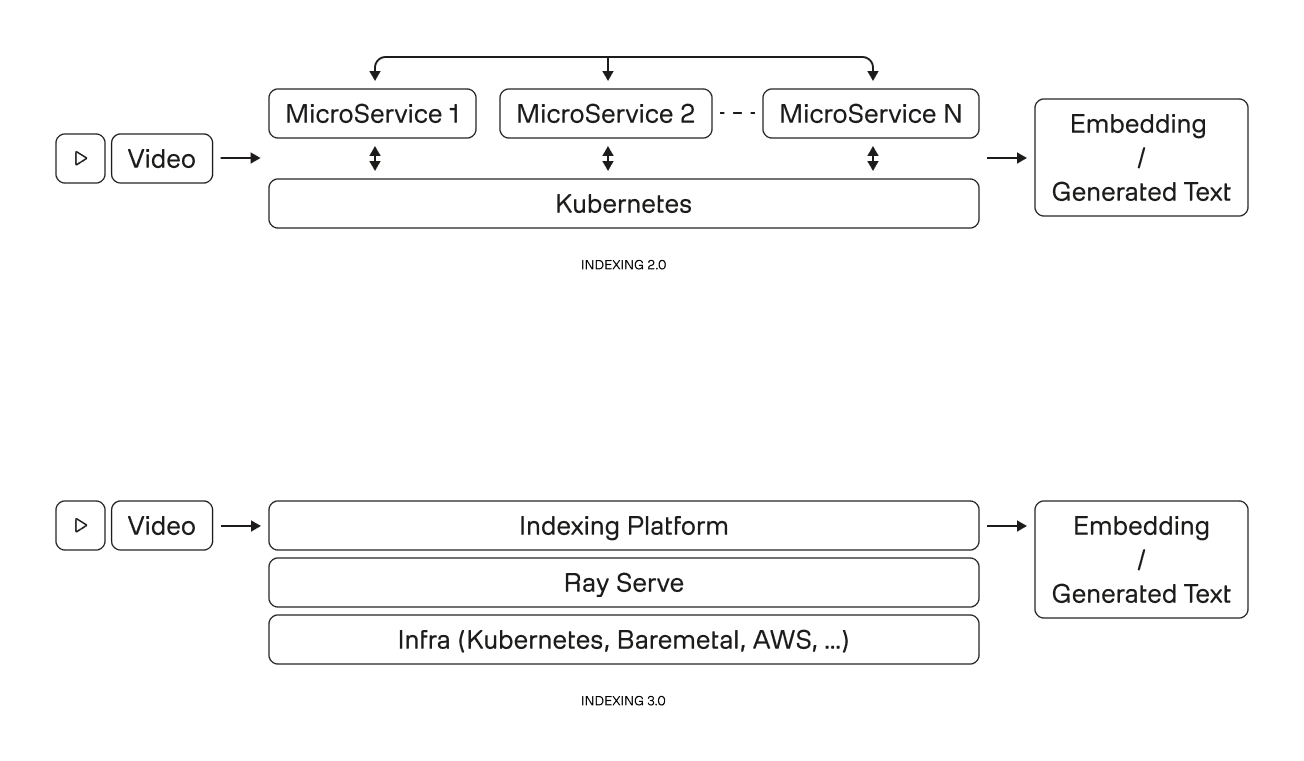

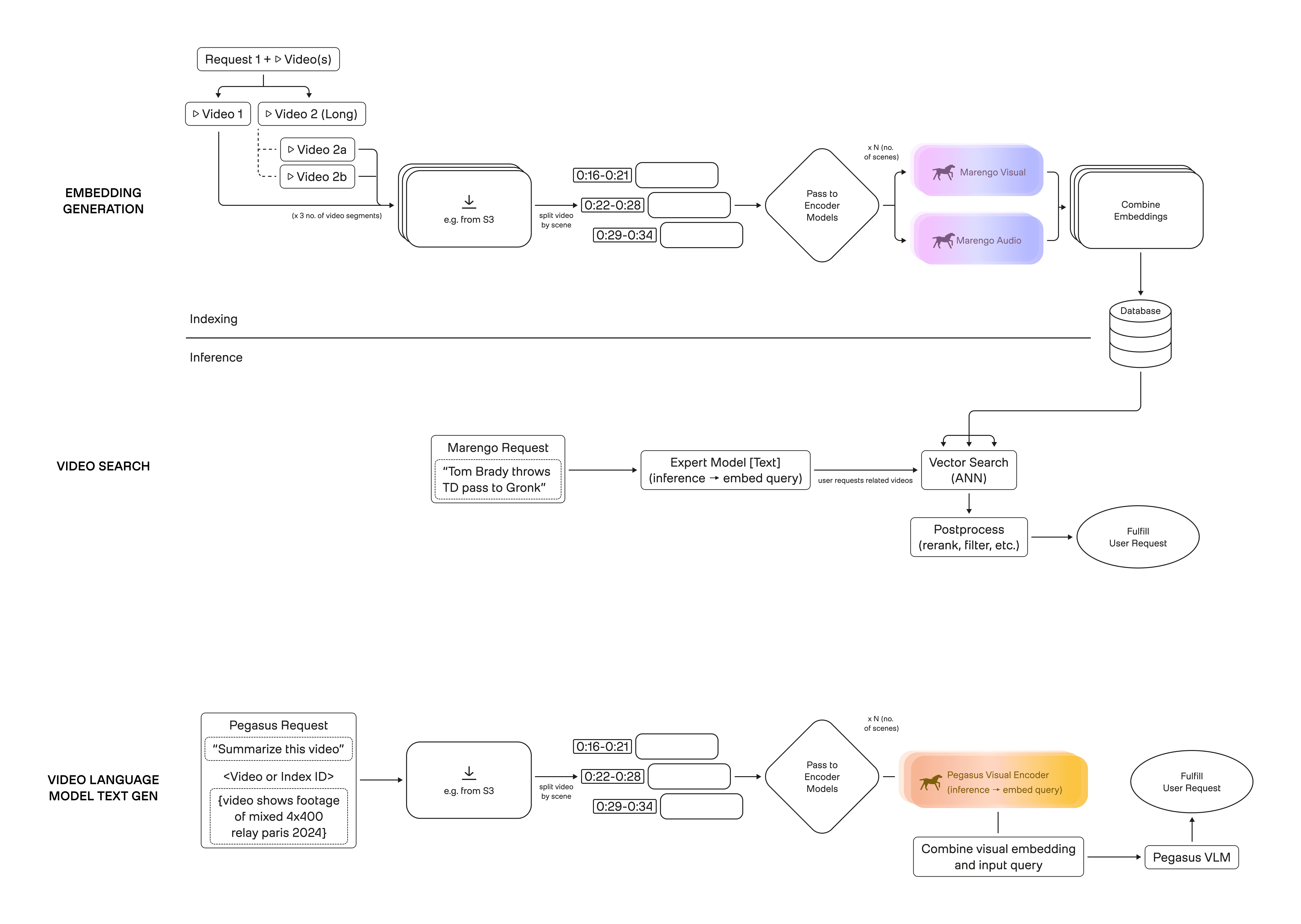

Figure 2. Indexing architecture shift: from a Kubernetes-coupled microservices mesh (2.0) to a layered platform with a unified execution layer (3.0).

3.2 - A different question: what should be layered, and what should not?

Indexing 3.0 began with a different framing.

Instead of asking how to decompose the system into smaller services, we asked:

Which responsibilities actually need to be distributed, and which need to stay conceptually unified?

That led to a layered mental model, illustrated in the “mesh vs layers” diagram above:

At the top sits the indexing platform itself—the logic that understands how video should be processed, how work is sequenced, and what constitutes a completed result.

In the middle is a unifying execution and orchestration layer (Ray Serve in our case) - responsible for scaling, scheduling, and fault handling without leaking infrastructure details upward.

At the bottom is the infrastructure layer—the compute substrate (Kubernetes, Baremetal, AWS, etc.)—which is treated as interchangeable rather than defining.

The shift is not “fewer boxes.” It’s clean directionality: work flows down through layers; infrastructure concerns don’t leak upward.

3.3 - Make it concrete: the indexing 3.0 data flow

Why is a layered architecture fits the shape of the indexing works?

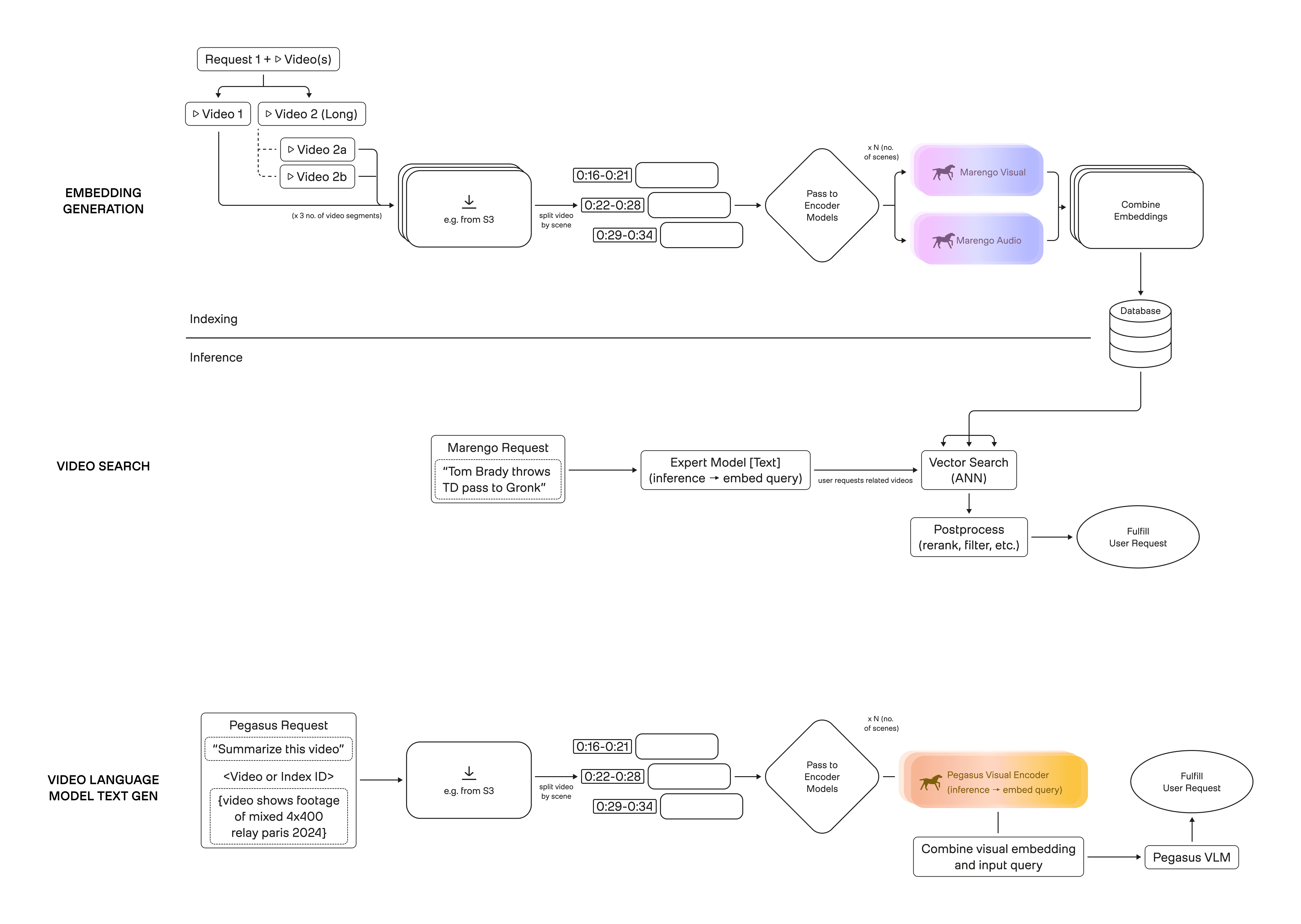

The diagram below shows indexing as three reusable primitives that power the product surfaces people actually interact with:

Figure 3. Three primitives powered by the same index: embedding generation → storage, text-to-video search via vector retrieval, and video-language generation via cached embeddings.

(1) Embedding generation (turn video into reusable representations)

At a high level, indexing starts by taking one request with one or more videos and turning each video into embeddings that can be reused across many downstream calls.

Conceptually, the flow is:

Video(s) → download

Split into logical segments (e.g., scenes; the point is “time becomes addressable”)

Pass segments to encoder models

Produce multimodal embeddings (e.g., visual + audio)

Combine + persist embeddings (and minimal metadata) into a database

This is the core “video → index” transformation. Everything else in the system is downstream reuse of these cached representations.

(2) Video search (turn a text query into retrieval over the index)

Search becomes straightforward once the index exists:

Text query → embed the query (in the same representation space as the video embeddings)

Vector search over stored embeddings to retrieve candidate matches

Post-process results (rerank, filter, apply simple constraints)

Return relevant clips/moments

The important point here is architectural: search is not “video processing” every time. It is retrieval over precomputed representations, plus lightweight post-processing.

(3) Video-language generation (reuse embeddings as context for a VLM)

Generation follows a similar reuse pattern, but routes the retrieved/cached representations into a decoder:

Request (prompt + video or index reference)

If embeddings exist, reuse them; otherwise, run the same embedding generation flow

Combine visual embeddings + the user’s input

Decode to text (video-language model)

Return the response

The key takeaway is that indexing is the shared substrate. Embedding generation produces reusable “addresses” into video. Search consumes those addresses via retrieval. Generation consumes them as context for reasoning.

That’s why the layered architecture matters. If you treat indexing as a collection of microservices stitched together by infrastructure, you pay coordination costs repeatedly across all three product paths. If you treat it as a coherent application flow running atop an execution layer and a swappable infrastructure substrate, you can evolve the shared substrate once—and every downstream surface benefits.

3.4 - Why layering changed everything

This reframe had several compounding effects.

First, it restored local reasoning. Engineers could understand and modify indexing behavior by looking at one place, rather than reconstructing intent from interactions across services.

Second, it made deployment a property of the bottom layer—not a constraint on the entire system. Swapping infrastructure no longer implied rewriting application logic.

Third, it aligned the architecture with how video workloads actually behave. Indexing is not a set of loosely related requests—it is a coordinated, end-to-end transformation. Treating it as such reduced the accidental complexity introduced by over-decomposition.

Most importantly, this shift changed what it meant to “scale” the system. Scaling no longer meant adding more services or more orchestration logic. It meant scaling the clarity of the system itself—so more people, more environments, and more future capabilities could be supported without compounding fragility.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into the design choices that made this layered model real in practice: consolidation, packaging, the trade-offs of a unifying execution layer, migration strategy, and supporting multiple deployment environments without fragmentation.

Introduction — Indexing is where video becomes usable

Video is a uniquely punishing input for production systems. It’s high bandwidth, long-lived, and multimodal—pixels, audio, speech, motion, and timing all matter. More importantly, the “unit of work” isn’t a single inference call. Indexing is an end-to-end transformation: take an opaque blob of video and turn it into structured representations that downstream systems can query reliably.

That boundary layer—indexing—is where video becomes usable.

As TwelveLabs grew, indexing moved from “the thing that runs in the background” to a core piece of infrastructure that every product surface depends on. Search and generation don’t just consume model outputs; they consume the indexing system’s guarantees: what gets processed, how consistently, how debuggably, and how deployably.

And that’s where we hit the breaking point.

Our earlier indexing platform (internally, “Indexing 2.0”) wasn’t failing in the obvious ways. It could process videos. It powered real workloads. But its architecture carried assumptions that became limiting as our team and deployment needs expanded: coordination costs rose, infrastructure coupling hardened, and the system became harder for new engineers to reason about end-to-end.

Indexing 3.0 is our response—but it’s not a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s an architectural reframe: from a microservices mesh that implicitly depended on a specific operating environment, to a layered system designed to scale engineering throughput and run across multiple deployment shapes.

In this post, we’ll walk through the thinking behind Indexing 3.0: what stopped scaling in the previous approach, what actually drove the rebuild, and how the “mesh → layers” model became the organizing idea for everything that followed.

Figure 1. High-level embedding flow: decode video/audio, detect scene boundaries, then embed visual, audio, and transcript segments.

1 - The real breaking point: why our earlier indexing system stopped scaling

Before Indexing 3.0, TwelveLabs operated an earlier generation of our video indexing platform—what we’ll refer to here simply as Indexing 2.0. Like many early-stage production ML platforms, it was designed to solve a very real problem at the time: reliably transforming raw video into usable representations at scale.

And by that definition, it worked.

It powered real workloads, supported multiple model capabilities, and enabled core product surfaces. But as the company grew, a different kind of pressure surfaced—one that had less to do with model quality and more to do with how the system behaved operationally and how it scaled as an organization.

A useful way to see why is to look at what indexing actually has to do end-to-end. It’s a coordinated flow that turns a video asset into cached representations that downstream systems (search and text generation) can use repeatedly.

1.1 - When microservices stop feeling modular

Over time, the Indexing 2.0 platform evolved into a distributed collection of services, each responsible for a specific part of the indexing process. On paper, that decomposition looked clean and modular. In practice, it introduced a form of complexity that compounded with every change.

A small feature update often required touching multiple services. Releases had to be coordinated. Debugging required reconstructing behavior across boundaries instead of reasoning about a single flow. What initially felt flexible slowly became rigid—not because any one service was poorly designed, but because the system as a whole had too many moving parts.

One additional multiplier here was runtime and language boundaries. Some components written in Golang naturally lived closer to production plumbing, while others written in Python lived closer to ML workflows—and the interface between them wasn’t always clean. Crossing that boundary repeatedly (data formats, error propagation, tracing/observability, retries, deployment artifacts) made the “distributed modularity” feel less like separation of concerns and more like separation of context.

At a certain point, the cost of coordination overtook the benefits of decomposition.

1.2 - Infrastructure and scaling assumptions become visible in the worst case scenario

A deeper issue emerged as the system matured: application behavior became coupled to infrastructure behavior.

One example was a scaling pattern that is extremely flexible but can become operationally expensive: spinning up resources per video. That design can be a reasonable default when workloads skew toward longer jobs and when isolation is valuable. Each video becomes a self-contained unit of scheduling and execution.

But the workload reality changes as products mature.

When workloads include a high proportion of very short videos, per-video orchestration overhead starts to dominate:

scheduling and startup costs become a larger fraction of end-to-end time,

scaling down cleanly becomes harder (resource churn and minimum footprints),

and you can end up paying “setup tax” repeatedly for work that finishes quickly.

In other words, a pattern optimized for flexibility at the unit-of-video granularity can behave poorly when the unit of work gets small. This isn’t a “bug,” it’s a mismatch between execution granularity and workload distribution—and it’s exactly the kind of mismatch that only reveals itself after a system hits real product scale.

1.3 - The human scalability ceiling

Perhaps the most telling signal was not an outage or a performance regression, but a people problem.

As the team grew, fewer engineers were able to comfortably reason about the full indexing flow. Understanding how a change propagated through the system required deep, accumulated context. Onboarding became slower. Contributions clustered around a small set of specialists.

Indexing 2.0 had reached a point where it could scale compute, but not contributors. That’s the inflection point we associate with “stopped scaling”: the system continues to run, but it becomes increasingly hard to evolve—especially when product requirements shift (deployment environments diversify, workloads change shape, new model capabilities arrive).

For our ML Infrastructure team at TwelveLabs, this was the moment we realized that incremental improvements would no longer be enough. To move forward, we needed to rethink indexing not as a collection of services, but as a coherent, portable system that could scale teams, deployments, and future capabilities together.

That realization set the stage for Indexing 3.0.

2 - What actually drove Indexing 3.0

Once we accepted that the bottleneck was organizational and operational—not just computational—we had to get precise about what we were optimizing for next.

Indexing 3.0 is our name for the architectural response. It isn’t a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s a deliberate rebuild designed around new constraints: more teams shipping in parallel, more deployment environments, and workload shapes (like short video) that stress different parts of the system.

Three drivers emerged clearly—and in a different priority order than we initially expected.

2.1 - Scaling engineering throughput, not just compute

The primary driver behind Indexing 3.0 was maintainability, but not in the abstract sense of “clean code.”

What mattered was engineering throughput: how many people could make changes confidently, how quickly new contributors could form a mental model of the system, and how safely teams could work in parallel without stepping on each other.

This is where the earlier polyglot / multi-service shape mattered. Even when each component was individually understandable, the interfaces were where complexity accumulated: data contracts, serialization, failure semantics, tracing, deployment packaging. Indexing 3.0 explicitly treats reducing those boundaries as a first-class lever for velocity.

2.2 - Packaging and deployment became first-order constraints

A second, business-critical driver followed closely behind: deployment flexibility.

As TwelveLabs expanded into new environments, it became clear that assumptions baked into the earlier system no longer held. Some environments offered full orchestration platforms. Others allowed only minimal container execution. Treating these as edge cases would have limited where the product could realistically ship.

This forced a shift in perspective:

Instead of “how do we deploy this system?”, we asked: what does the system assume about where it runs?

Indexing 3.0 is designed so deployment shape becomes a variable, not a defining feature of the architecture.

This matters because indexing isn’t a standalone service—it’s the substrate beneath multiple downstream products. Since we offer two video foundation models (Marengo and Pegasus) with different capabilities, the same indexed representations can power retrieval-style workloads (search) and reasoning-style workloads (analysis). Portability expands what products can exist and where they can ship.

2.3 - Cost as a structural outcome, not a tuning exercise

Cost was an important consideration, but notably, it was not the starting point.

In earlier iterations, cost optimizations had largely taken the form of incremental tuning—adjusting resource usage, tweaking configurations, or reacting to specific bottlenecks. Indexing 3.0 took a different approach.

The team recognized that many cost issues were symptoms of deeper structural choices: too many always-on components, inefficient coordination between stages, and architectures that made it difficult to right-size resources independently.

Rather than chasing isolated savings, Indexing 3.0 aimed to create an architecture where efficiency emerged naturally from simpler execution paths, clearer scaling boundaries, and more flexible deployment models.

2.4 - A change in what “success” meant

Taken together, these drivers led to a subtle but important shift in how success was defined.

Indexing 3.0 would not be judged primarily by raw performance numbers or by how novel the architecture looked on paper. It would be judged by whether it enabled:

Faster onboarding and safer contributions,

Parallel development without constant coordination,

Consistent behavior across environments,

The ability to evolve without repeated rewrites.

In the next section, we’ll look at how this shift in priorities led to a fundamentally different way of thinking about the indexing architecture itself.

3 - The architectural reframe: from “microservices mesh” to “streamlined layers”

Once the drivers behind Indexing 3.0 were clear, the next step was to confront a harder truth: the existing architecture was optimized for a different set of assumptions than the ones the business now faced.

What needed to change was not a single component, but the shape of the system itself.

3.1 - The problem with the “microservices mesh”

The earlier indexing platform followed a pattern that will be familiar to many teams: break the system into many small services, connect them through orchestration and routing layers, and let the infrastructure manage execution.

Over time, this created what we now think of as a microservices mesh.

work flows sideways as much as forward,

coordination logic spreads across services and control-plane interactions,

and understanding “what happens to a request” requires global context.

This approach has advantages early on. It allows teams to move independently and scale components in isolation. But as the indexing system grows—and especially as workloads become more heterogeneous—those advantages erode.

Even at a high level, indexing involves decoding, segmentation, embedding, and persistence steps that must compose correctly. When each step is its own service boundary, the system becomes harder to debug, harder to package, and harder to evolve.

Figure 2. Indexing architecture shift: from a Kubernetes-coupled microservices mesh (2.0) to a layered platform with a unified execution layer (3.0).

3.2 - A different question: what should be layered, and what should not?

Indexing 3.0 began with a different framing.

Instead of asking how to decompose the system into smaller services, we asked:

Which responsibilities actually need to be distributed, and which need to stay conceptually unified?

That led to a layered mental model, illustrated in the “mesh vs layers” diagram above:

At the top sits the indexing platform itself—the logic that understands how video should be processed, how work is sequenced, and what constitutes a completed result.

In the middle is a unifying execution and orchestration layer (Ray Serve in our case) - responsible for scaling, scheduling, and fault handling without leaking infrastructure details upward.

At the bottom is the infrastructure layer—the compute substrate (Kubernetes, Baremetal, AWS, etc.)—which is treated as interchangeable rather than defining.

The shift is not “fewer boxes.” It’s clean directionality: work flows down through layers; infrastructure concerns don’t leak upward.

3.3 - Make it concrete: the indexing 3.0 data flow

Why is a layered architecture fits the shape of the indexing works?

The diagram below shows indexing as three reusable primitives that power the product surfaces people actually interact with:

Figure 3. Three primitives powered by the same index: embedding generation → storage, text-to-video search via vector retrieval, and video-language generation via cached embeddings.

(1) Embedding generation (turn video into reusable representations)

At a high level, indexing starts by taking one request with one or more videos and turning each video into embeddings that can be reused across many downstream calls.

Conceptually, the flow is:

Video(s) → download

Split into logical segments (e.g., scenes; the point is “time becomes addressable”)

Pass segments to encoder models

Produce multimodal embeddings (e.g., visual + audio)

Combine + persist embeddings (and minimal metadata) into a database

This is the core “video → index” transformation. Everything else in the system is downstream reuse of these cached representations.

(2) Video search (turn a text query into retrieval over the index)

Search becomes straightforward once the index exists:

Text query → embed the query (in the same representation space as the video embeddings)

Vector search over stored embeddings to retrieve candidate matches

Post-process results (rerank, filter, apply simple constraints)

Return relevant clips/moments

The important point here is architectural: search is not “video processing” every time. It is retrieval over precomputed representations, plus lightweight post-processing.

(3) Video-language generation (reuse embeddings as context for a VLM)

Generation follows a similar reuse pattern, but routes the retrieved/cached representations into a decoder:

Request (prompt + video or index reference)

If embeddings exist, reuse them; otherwise, run the same embedding generation flow

Combine visual embeddings + the user’s input

Decode to text (video-language model)

Return the response

The key takeaway is that indexing is the shared substrate. Embedding generation produces reusable “addresses” into video. Search consumes those addresses via retrieval. Generation consumes them as context for reasoning.

That’s why the layered architecture matters. If you treat indexing as a collection of microservices stitched together by infrastructure, you pay coordination costs repeatedly across all three product paths. If you treat it as a coherent application flow running atop an execution layer and a swappable infrastructure substrate, you can evolve the shared substrate once—and every downstream surface benefits.

3.4 - Why layering changed everything

This reframe had several compounding effects.

First, it restored local reasoning. Engineers could understand and modify indexing behavior by looking at one place, rather than reconstructing intent from interactions across services.

Second, it made deployment a property of the bottom layer—not a constraint on the entire system. Swapping infrastructure no longer implied rewriting application logic.

Third, it aligned the architecture with how video workloads actually behave. Indexing is not a set of loosely related requests—it is a coordinated, end-to-end transformation. Treating it as such reduced the accidental complexity introduced by over-decomposition.

Most importantly, this shift changed what it meant to “scale” the system. Scaling no longer meant adding more services or more orchestration logic. It meant scaling the clarity of the system itself—so more people, more environments, and more future capabilities could be supported without compounding fragility.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into the design choices that made this layered model real in practice: consolidation, packaging, the trade-offs of a unifying execution layer, migration strategy, and supporting multiple deployment environments without fragmentation.

Introduction — Indexing is where video becomes usable

Video is a uniquely punishing input for production systems. It’s high bandwidth, long-lived, and multimodal—pixels, audio, speech, motion, and timing all matter. More importantly, the “unit of work” isn’t a single inference call. Indexing is an end-to-end transformation: take an opaque blob of video and turn it into structured representations that downstream systems can query reliably.

That boundary layer—indexing—is where video becomes usable.

As TwelveLabs grew, indexing moved from “the thing that runs in the background” to a core piece of infrastructure that every product surface depends on. Search and generation don’t just consume model outputs; they consume the indexing system’s guarantees: what gets processed, how consistently, how debuggably, and how deployably.

And that’s where we hit the breaking point.

Our earlier indexing platform (internally, “Indexing 2.0”) wasn’t failing in the obvious ways. It could process videos. It powered real workloads. But its architecture carried assumptions that became limiting as our team and deployment needs expanded: coordination costs rose, infrastructure coupling hardened, and the system became harder for new engineers to reason about end-to-end.

Indexing 3.0 is our response—but it’s not a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s an architectural reframe: from a microservices mesh that implicitly depended on a specific operating environment, to a layered system designed to scale engineering throughput and run across multiple deployment shapes.

In this post, we’ll walk through the thinking behind Indexing 3.0: what stopped scaling in the previous approach, what actually drove the rebuild, and how the “mesh → layers” model became the organizing idea for everything that followed.

Figure 1. High-level embedding flow: decode video/audio, detect scene boundaries, then embed visual, audio, and transcript segments.

1 - The real breaking point: why our earlier indexing system stopped scaling

Before Indexing 3.0, TwelveLabs operated an earlier generation of our video indexing platform—what we’ll refer to here simply as Indexing 2.0. Like many early-stage production ML platforms, it was designed to solve a very real problem at the time: reliably transforming raw video into usable representations at scale.

And by that definition, it worked.

It powered real workloads, supported multiple model capabilities, and enabled core product surfaces. But as the company grew, a different kind of pressure surfaced—one that had less to do with model quality and more to do with how the system behaved operationally and how it scaled as an organization.

A useful way to see why is to look at what indexing actually has to do end-to-end. It’s a coordinated flow that turns a video asset into cached representations that downstream systems (search and text generation) can use repeatedly.

1.1 - When microservices stop feeling modular

Over time, the Indexing 2.0 platform evolved into a distributed collection of services, each responsible for a specific part of the indexing process. On paper, that decomposition looked clean and modular. In practice, it introduced a form of complexity that compounded with every change.

A small feature update often required touching multiple services. Releases had to be coordinated. Debugging required reconstructing behavior across boundaries instead of reasoning about a single flow. What initially felt flexible slowly became rigid—not because any one service was poorly designed, but because the system as a whole had too many moving parts.

One additional multiplier here was runtime and language boundaries. Some components written in Golang naturally lived closer to production plumbing, while others written in Python lived closer to ML workflows—and the interface between them wasn’t always clean. Crossing that boundary repeatedly (data formats, error propagation, tracing/observability, retries, deployment artifacts) made the “distributed modularity” feel less like separation of concerns and more like separation of context.

At a certain point, the cost of coordination overtook the benefits of decomposition.

1.2 - Infrastructure and scaling assumptions become visible in the worst case scenario

A deeper issue emerged as the system matured: application behavior became coupled to infrastructure behavior.

One example was a scaling pattern that is extremely flexible but can become operationally expensive: spinning up resources per video. That design can be a reasonable default when workloads skew toward longer jobs and when isolation is valuable. Each video becomes a self-contained unit of scheduling and execution.

But the workload reality changes as products mature.

When workloads include a high proportion of very short videos, per-video orchestration overhead starts to dominate:

scheduling and startup costs become a larger fraction of end-to-end time,

scaling down cleanly becomes harder (resource churn and minimum footprints),

and you can end up paying “setup tax” repeatedly for work that finishes quickly.

In other words, a pattern optimized for flexibility at the unit-of-video granularity can behave poorly when the unit of work gets small. This isn’t a “bug,” it’s a mismatch between execution granularity and workload distribution—and it’s exactly the kind of mismatch that only reveals itself after a system hits real product scale.

1.3 - The human scalability ceiling

Perhaps the most telling signal was not an outage or a performance regression, but a people problem.

As the team grew, fewer engineers were able to comfortably reason about the full indexing flow. Understanding how a change propagated through the system required deep, accumulated context. Onboarding became slower. Contributions clustered around a small set of specialists.

Indexing 2.0 had reached a point where it could scale compute, but not contributors. That’s the inflection point we associate with “stopped scaling”: the system continues to run, but it becomes increasingly hard to evolve—especially when product requirements shift (deployment environments diversify, workloads change shape, new model capabilities arrive).

For our ML Infrastructure team at TwelveLabs, this was the moment we realized that incremental improvements would no longer be enough. To move forward, we needed to rethink indexing not as a collection of services, but as a coherent, portable system that could scale teams, deployments, and future capabilities together.

That realization set the stage for Indexing 3.0.

2 - What actually drove Indexing 3.0

Once we accepted that the bottleneck was organizational and operational—not just computational—we had to get precise about what we were optimizing for next.

Indexing 3.0 is our name for the architectural response. It isn’t a “version upgrade” in the product sense. It’s a deliberate rebuild designed around new constraints: more teams shipping in parallel, more deployment environments, and workload shapes (like short video) that stress different parts of the system.

Three drivers emerged clearly—and in a different priority order than we initially expected.

2.1 - Scaling engineering throughput, not just compute

The primary driver behind Indexing 3.0 was maintainability, but not in the abstract sense of “clean code.”

What mattered was engineering throughput: how many people could make changes confidently, how quickly new contributors could form a mental model of the system, and how safely teams could work in parallel without stepping on each other.

This is where the earlier polyglot / multi-service shape mattered. Even when each component was individually understandable, the interfaces were where complexity accumulated: data contracts, serialization, failure semantics, tracing, deployment packaging. Indexing 3.0 explicitly treats reducing those boundaries as a first-class lever for velocity.

2.2 - Packaging and deployment became first-order constraints

A second, business-critical driver followed closely behind: deployment flexibility.

As TwelveLabs expanded into new environments, it became clear that assumptions baked into the earlier system no longer held. Some environments offered full orchestration platforms. Others allowed only minimal container execution. Treating these as edge cases would have limited where the product could realistically ship.

This forced a shift in perspective:

Instead of “how do we deploy this system?”, we asked: what does the system assume about where it runs?

Indexing 3.0 is designed so deployment shape becomes a variable, not a defining feature of the architecture.

This matters because indexing isn’t a standalone service—it’s the substrate beneath multiple downstream products. Since we offer two video foundation models (Marengo and Pegasus) with different capabilities, the same indexed representations can power retrieval-style workloads (search) and reasoning-style workloads (analysis). Portability expands what products can exist and where they can ship.

2.3 - Cost as a structural outcome, not a tuning exercise

Cost was an important consideration, but notably, it was not the starting point.

In earlier iterations, cost optimizations had largely taken the form of incremental tuning—adjusting resource usage, tweaking configurations, or reacting to specific bottlenecks. Indexing 3.0 took a different approach.

The team recognized that many cost issues were symptoms of deeper structural choices: too many always-on components, inefficient coordination between stages, and architectures that made it difficult to right-size resources independently.

Rather than chasing isolated savings, Indexing 3.0 aimed to create an architecture where efficiency emerged naturally from simpler execution paths, clearer scaling boundaries, and more flexible deployment models.

2.4 - A change in what “success” meant

Taken together, these drivers led to a subtle but important shift in how success was defined.

Indexing 3.0 would not be judged primarily by raw performance numbers or by how novel the architecture looked on paper. It would be judged by whether it enabled:

Faster onboarding and safer contributions,

Parallel development without constant coordination,

Consistent behavior across environments,

The ability to evolve without repeated rewrites.

In the next section, we’ll look at how this shift in priorities led to a fundamentally different way of thinking about the indexing architecture itself.

3 - The architectural reframe: from “microservices mesh” to “streamlined layers”

Once the drivers behind Indexing 3.0 were clear, the next step was to confront a harder truth: the existing architecture was optimized for a different set of assumptions than the ones the business now faced.

What needed to change was not a single component, but the shape of the system itself.

3.1 - The problem with the “microservices mesh”

The earlier indexing platform followed a pattern that will be familiar to many teams: break the system into many small services, connect them through orchestration and routing layers, and let the infrastructure manage execution.

Over time, this created what we now think of as a microservices mesh.

work flows sideways as much as forward,

coordination logic spreads across services and control-plane interactions,

and understanding “what happens to a request” requires global context.

This approach has advantages early on. It allows teams to move independently and scale components in isolation. But as the indexing system grows—and especially as workloads become more heterogeneous—those advantages erode.

Even at a high level, indexing involves decoding, segmentation, embedding, and persistence steps that must compose correctly. When each step is its own service boundary, the system becomes harder to debug, harder to package, and harder to evolve.

Figure 2. Indexing architecture shift: from a Kubernetes-coupled microservices mesh (2.0) to a layered platform with a unified execution layer (3.0).

3.2 - A different question: what should be layered, and what should not?

Indexing 3.0 began with a different framing.

Instead of asking how to decompose the system into smaller services, we asked:

Which responsibilities actually need to be distributed, and which need to stay conceptually unified?

That led to a layered mental model, illustrated in the “mesh vs layers” diagram above:

At the top sits the indexing platform itself—the logic that understands how video should be processed, how work is sequenced, and what constitutes a completed result.

In the middle is a unifying execution and orchestration layer (Ray Serve in our case) - responsible for scaling, scheduling, and fault handling without leaking infrastructure details upward.

At the bottom is the infrastructure layer—the compute substrate (Kubernetes, Baremetal, AWS, etc.)—which is treated as interchangeable rather than defining.

The shift is not “fewer boxes.” It’s clean directionality: work flows down through layers; infrastructure concerns don’t leak upward.

3.3 - Make it concrete: the indexing 3.0 data flow

Why is a layered architecture fits the shape of the indexing works?

The diagram below shows indexing as three reusable primitives that power the product surfaces people actually interact with:

Figure 3. Three primitives powered by the same index: embedding generation → storage, text-to-video search via vector retrieval, and video-language generation via cached embeddings.

(1) Embedding generation (turn video into reusable representations)

At a high level, indexing starts by taking one request with one or more videos and turning each video into embeddings that can be reused across many downstream calls.

Conceptually, the flow is:

Video(s) → download

Split into logical segments (e.g., scenes; the point is “time becomes addressable”)

Pass segments to encoder models

Produce multimodal embeddings (e.g., visual + audio)

Combine + persist embeddings (and minimal metadata) into a database

This is the core “video → index” transformation. Everything else in the system is downstream reuse of these cached representations.

(2) Video search (turn a text query into retrieval over the index)

Search becomes straightforward once the index exists:

Text query → embed the query (in the same representation space as the video embeddings)

Vector search over stored embeddings to retrieve candidate matches

Post-process results (rerank, filter, apply simple constraints)

Return relevant clips/moments

The important point here is architectural: search is not “video processing” every time. It is retrieval over precomputed representations, plus lightweight post-processing.

(3) Video-language generation (reuse embeddings as context for a VLM)

Generation follows a similar reuse pattern, but routes the retrieved/cached representations into a decoder:

Request (prompt + video or index reference)

If embeddings exist, reuse them; otherwise, run the same embedding generation flow

Combine visual embeddings + the user’s input

Decode to text (video-language model)

Return the response

The key takeaway is that indexing is the shared substrate. Embedding generation produces reusable “addresses” into video. Search consumes those addresses via retrieval. Generation consumes them as context for reasoning.

That’s why the layered architecture matters. If you treat indexing as a collection of microservices stitched together by infrastructure, you pay coordination costs repeatedly across all three product paths. If you treat it as a coherent application flow running atop an execution layer and a swappable infrastructure substrate, you can evolve the shared substrate once—and every downstream surface benefits.

3.4 - Why layering changed everything

This reframe had several compounding effects.

First, it restored local reasoning. Engineers could understand and modify indexing behavior by looking at one place, rather than reconstructing intent from interactions across services.

Second, it made deployment a property of the bottom layer—not a constraint on the entire system. Swapping infrastructure no longer implied rewriting application logic.

Third, it aligned the architecture with how video workloads actually behave. Indexing is not a set of loosely related requests—it is a coordinated, end-to-end transformation. Treating it as such reduced the accidental complexity introduced by over-decomposition.

Most importantly, this shift changed what it meant to “scale” the system. Scaling no longer meant adding more services or more orchestration logic. It meant scaling the clarity of the system itself—so more people, more environments, and more future capabilities could be supported without compounding fragility.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into the design choices that made this layered model real in practice: consolidation, packaging, the trade-offs of a unifying execution layer, migration strategy, and supporting multiple deployment environments without fragmentation.

Related articles

© 2021

-

2026

TwelveLabs, Inc. All Rights Reserved

© 2021

-

2026

TwelveLabs, Inc. All Rights Reserved

© 2021

-

2026

TwelveLabs, Inc. All Rights Reserved